As another blur of a weekend draws to a close, one of the highlights was taking the family out to dine at a new local eatery. The place in question had invited other local business owners to eat there before their formal opening. This is a common trail run approach, to test procedures with a set of friendly customers with final pre-flight checks.

One point of note was the table ordering system. It’s no longer remarkable to order to the table from an app (especially in these post-pandemic times, where we have got accustomed to reduced interaction in the service industries). The general flow appeared to be to scan an QR code, which directed the device to download an app. The app is then accessed by providing consent to use my usual webmail provider for access. Again, largely unremarkable, which is a sign of the success of underlying protocols at play, like OAuth2 and OIDC. In an area of technology that has witnessed a plethora of standards over the past few decades, OAuth2 and OIDC have established themselves as the de-facto standard for end user Identity and access sharing*.

OAuth2 is all about resource access and sharing.

Being able to authorize my online email account to share data and provide access to a completely disparate app is one of the typical capabilities provided by OAuth2. OAuth2 enables functionality and data to be shared between online services given appropriate consent provided by the end user.

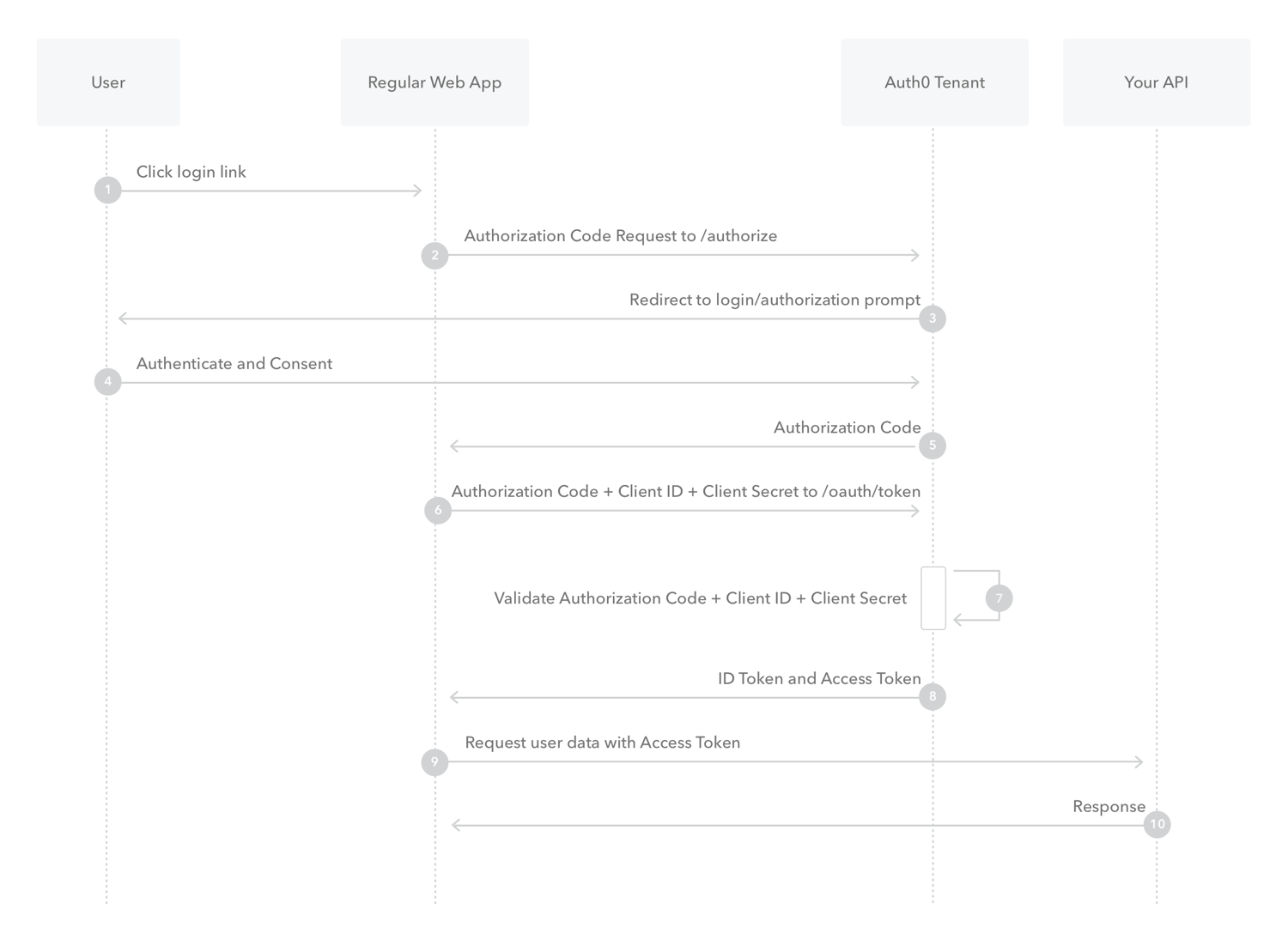

The flow to direct authorization and access is well documented here, though the diagram describing the sequence of interactions is included below for ease.

As can be seen from the auth flow above. OAuth2 allows for user granted access to resources by providing specific URLs (/authorize and /token) to allow the user to be redirected to confirm access, and serve access tokens . Other flows exist for OAuth, though the above describes the typical authorization flow, and is quite front channel centric (using client redirects and requiring user interaction).

OAuth2 is front channel centric

This reasonably dates and couches OAuth2 to the desktop age. With the explosion of mobile devices and management of asymmetric cryptography getting easier and less esoteric, additions to OAuth have emerged to tackle the various limitations of functionality and usability and form a rich ecosystem, (eg. PKCE for mobile and client applications, and the pirate protocols of PAR, RAR and JAR to increase flexibility, scoping flexibility and and securely authorising requests).

OAuth2.1 specification encapsulates the best practices from OAuth2, removing the unused and deprecated features and embedding the standard extension points.

The emergence of the suite of best practice additions to OAuth2 (and deprecation of certain features such as ROPC) has been encapsulated in the OAuth2.1 spec. One of the most popular additions to OAuth is OpenId Connect, which adds authentication and identity features to the specification.

OpenID Connect (or OIDC for short) is an authentication extension to the OAuth2 adding Identity Features.

An OAuth provider with OIDC allows for authorization claims to be verified via an encoded (and usually signed) Java Web Token (JWT, pronounced ‘jot‘). Specifically the JWT called the ID token is used for this purpose. It’s probably worth some mention of what is meant by claims in this context. The general pattern for Identity, is for a User to make some sort of assertion (such as who they are, or qualification they might have etc), and to then verify that claim in some way (e.g. by answering knowledge based questions, or providing some sort of trusted evidence, such as a physical or digital document). Advances in cryptography and PKI have meant that a single (approved) source can issue a digital evidence, that can be read by all consumers and be considered tamper-proof. Anyway, back to normal service…

The ID token, stores authorization information (for example see here), though they often also include profile information claims of the user (such as name and/or email address details etc). To get additional profile details of for a user, OIDC specifies the /userinfo endpoint to retrieve these details (see here for an example).

Given the buffet of protocols, standards and additions to OAuth2.1, it forms a robust toolset for Identity and Authorization. However, in response to some of the longstanding limitations and issues raised by OAuth (see this youtube video for coverage of such criticisms), a emerging (compatibility breaking) standard iis starting to emerge in the form of GNAP (pronounced g’nap).

GNAP breaks compatibility with OAuth2 by implementing a new protocol, encapsulating the learnings and recommendations from OAuth2.1, while being future facing.

GNAP is not completely new, but has been an evolution of the an earlier initiative called TxAuth. For a future post, we’ll look into the GNAP specification and the emergence of Verifiable Credentials and shared signals!

For anyone who cannot wait for the next post, here’s some starter links and material to read ahead:

- ouath.xyz provides really useful information and links on GNAP

- Wikipedia has some mention of verifiable credentials here

- Shared signals are given a great intro here!

Hopefully this has been a useful overview of OAuth2, how it relates to OIDC and some of the possible directions of travel for the next iteration of Digital authorization and Identity!

* Alternative technologies in this area include SAML (which had been a popular choice around early 2001 or so for Enterprise identity sharing), and various WS- family of standards. See here for more details.

** See the Future of Auth for more links on GNAP and OAuth2.1.