This time, we follow up from the previous post where we looked at OAuth2 and OIDC flows. Effectively starting our interaction with the /authorize call and completing our journey at /token. These URLs (amongst others) are described at the bottom of this post. The OIDC journey took us from having a unauthenticated (aka AUTHN‘d) and unauthorised (AUTHZ‘d) user to one who had been granted access to some functionality from one website to another. Finally we included identity and authorization information using OIDC. In this post, we look at GNAP as a possible next generation in HTTP based delegation and Identity.

Some observations of OAuth2 are that it appears to be front channel centric and that it was something of a Grand Thali of identity dishes, requiring various, extensions and additions so that the spice may flow.

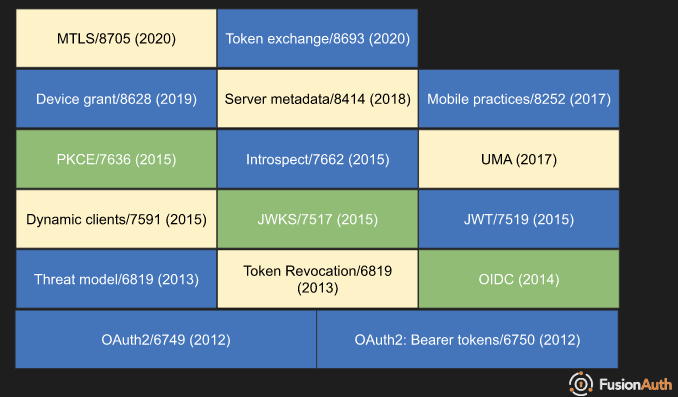

OAuth2 is a web centric framework that requires several extensions and additions to be useful.

A useful graphic from FusionAuth shows the typical stack of RFCs required to get started with OAuth2.

GNAP ambitiously tries to consolidate these features into a single spec, while also catering for several of the assumptions and constraints embedded in OAuth2. So what is GNAP? and how do you even say it?

On the latter point, our previous post suggested GNAP was pronounced as g’nap based upon this podcast episode. However, it appears the truth is not quite a lemon meringue but something slightly harder to swallow. In short, there had been much debate on how to pronounce GNAP, so it’s fair to assume that confidence is key to pronunciation here!

GNAP has a number of design goals around privacy and flexibility. It tackles these by adopting an interaction based model and is based on the use of cryptographic keys.

No matter, GNAP stands for the Grant Negotiation and Authorization Protocol, and is version 13 of its IETF draft at the time of writing. It is intended to provide a comprehensive authentication and authorization framework that can be used in a variety of contexts. Some of the features and goals of GNAP include, but are not limited too:

- Removing assumptions and reliance on interactions as being web browser initiated/based

- Allowing clients (aka requesting parties) and resource owners to be different users

- Treating interactions as a key building block in providing delegation and access

- Utilising PKI as a mechanism to dynamically bind clients and provide better privacy to end users and resources

- Enable greater granularity and control over access policies.

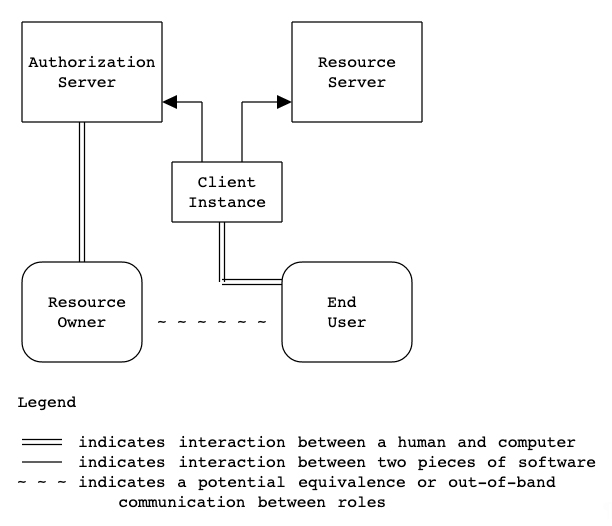

There are 5 key components that comprise the core of GNAP

Here is a brief overview of the main components in use for GNAP and their roles:

- End User: The party requesting access (aka the Requesting Party/Natural Person). May or may not also be the resource owner.

- Client Instance: Application acting on behalf of the End User.

- Resource Server: provides operations on protected resources.

- Authorization Server: serves access tokens and provides subject information (i.e. identity information)

- Resource Owner: the party that can grant/deny access to protected resources.

The GNAP flow is a multistage, stateful, process. Whereas the typical OAuth flow would start with an /authorize call, the GNAP process starts with calls to /interact. The Client here is not assumed to be a web browser, and the specification describes a number of different ways of interacting. These include an interaction flow being synchronous/asynchronous and requiring user interaction or be fully autonomous. Note, a /token endpoint is still assumed here in order to retrieve/refresh access tokens.

Access to multiple resources (and hence requesting multiple access tokens) can be made of a granular level by using a JSON based Grant Request. Requests for user information can also be embedded in the same request.

Client instances can dynamically bind to Authorization Servers using the client held crypto keys, which lifts the dependency of having a preconfigured client_secret.

When comms need to be followed up using the front channel, this is typically done by passing a reference and hash (as a tamper prevention mechanism), and using the interact_ref parameter. This both reduces the amount of information passed over the public channel for privacy and compactness purposes.

As a slight aside on privacy OAuth is often considered as at risk, given the amount of data held by a small number of digital gatekeepers (or Identity Providers IdPs). One of the GNAP authors offers an interesting perspective on this in his personal blog here. This has been one of the forces leading to the emergence of Decentralised identifiers and Self Sovereign Identity, which we’ll look at in more detail in the next post in which we look at the emergence of Verifiable Credentials. Digital verification might also provide one of the pieces in addressing the challenge of data provenance given the explosion of AI generated misinformation.

What next?

Hopefully, this gives enough of an overview of the intent and design of GNAP to pique some interest. There’s all the usual caveats around any emerging technology and standards, but there is also a wealth of prior art and investigation that has fed into GNAP to provide reasonably firm foundations. Given the explosion of mobile as gateway channel and the operational maturity of PKI in recent years, it feels like an appropriate time to look at how the AUTHN and AUTHZ stacks and developing in parallel.

Next time, we’ll look at Verifiable Credentials, before moving onto Shared Signals as a mechanism of sharing associated events between parties.

Further reading

Typical endpoints and where you find them..

| /authorize | Initial interaction endpoint with Authorization server | OAuth2 |

| /token | Endpoint to retrieve access tokens | OAuth2 GNAP |

| /introspect | Endpoint to retrieve access token meta info | OAuth2 GNAP |

| /userinfo | OIDC endpoint providing user details | OIDC |

| /interact | Initial and Main interaction endpoint with Auth Server | GNAP |